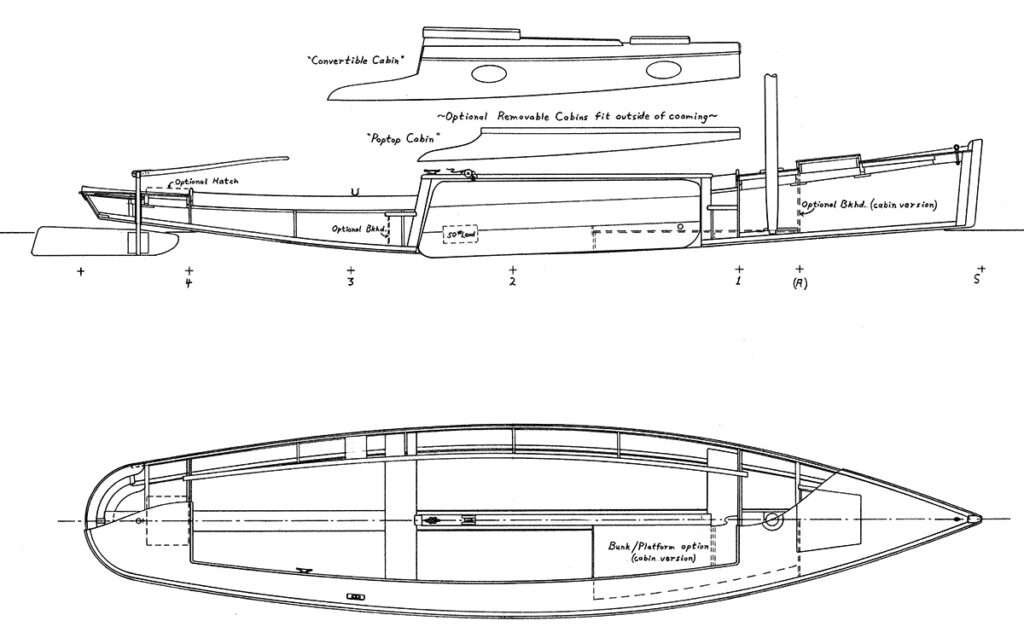

L.O.A.—27’ 10”

Beam—6’

Draft—8 ¾”

Sail Area—154 sq ft

Weight—1,500#

Of all the boats in The Sharpie Book, this one probably epitomizes the sharpie. I also feel that this is the most beautiful and fine-lined of all the craft, having excellent proportions and form. The model for my drawing is Fig. 39 from American Small Sailing Craft; I did not alter the original form in any way, except for minor details of construction.

The model is a late version of the one-man, or 100-bushel boat, as they commonly appeared in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. Chapelle states that the masts for these boats were spruce; they were commonly unstepped and stepped to pass under bridges. How one man did this is not explained—I have a little trouble imagining him just grabbing and unstepping a 27-foot mast! The way Chapelle puts it is: “In the old and small boats it was possible for a strong and active man to shift the masts from one step to another afloat, but this could not be done in the later sharpies.” Just make sure I’m not around when you try it! In Chapter Seven of The Sharpie Book I explain using the sprit as a gin pole to step masts.

Chapelle states that this particular model (taken from an abandoned hull in 1932 at New Haven) represents the most highly developed type of one-man sharpie. He also notes that her stern was slightly lower than the earlier models, giving her a better shape for yachting and racing.

I moved the aft thwart forward slightly, gave the rudder a little more area on top (I found it helped on Gato Negro), and drew the mast at 26 feet instead of 27. I also drew the forward bulkhead in full height, instead of stopping it at the thwart—this simplifies construction, as the bulkhead is used as a design station. In conjunction with the half-bulkhead just aft, a watertight box is formed under the thwart/step that can be used as a locker, or for floatation.

The traditional craft carried only one sail, with the mast raked very slightly—only 1/2 degree. I drew in an optional “balance” jib, borrowed from the Chesapeake, to be used as a light-air sail. I would recommend raking the mast somewhat more, to 5 degrees, if you opt to use this sail—otherwise the vessel will very likely have lee helm in light air. Another possibility is to shorten the mast height (decreasing mains’l size) and shift the centerboard trunk forward until the forward post is against the forward bulkhead, effectively converting the rig to a sloop.

Because the hull is very narrow and fine, it will be very easily driven, and probably needs no alteration of rig. Hence I would only recommend the balance jib if you live in an area of notoriously light air, or if you intend to race the boat. I also think this hull would “scale up” very nicely, to 50 or 60 feet, for use as an island cruising yacht. I would then rig her as a yawl, with shorter, raked mainmast, stem-head jib (on a stay), shrouds and backstay, and a moderate-sized mizzenmast with a sprit- or lug-rigged mizzen sail; or perhaps a rig a little like Clapham’s Roslyn Yawls.