MY PERSONAL CRUISING SAILBOATS

TERESA de Isla Morada

By Reuel Parker

TERESA de ISLA MORADA flying her kite on Chesapeake Bay, 1985

In early 1985 I leased an “abandoned” property on the south side of Windley Key, in Islamorada, Florida. It had three acres, a ruined fishing camp, and a 100-foot private canal and concrete dock. It had vacant lots on both sides, and it was very overgrown with indigenous shrubs and trees, coconut palms and casuarina (Australian) pines. It even had a huge tamarind tree. To me, it looked like Paradise! That was before we discovered the fire ants, huge green scorpions, and bull sharks….

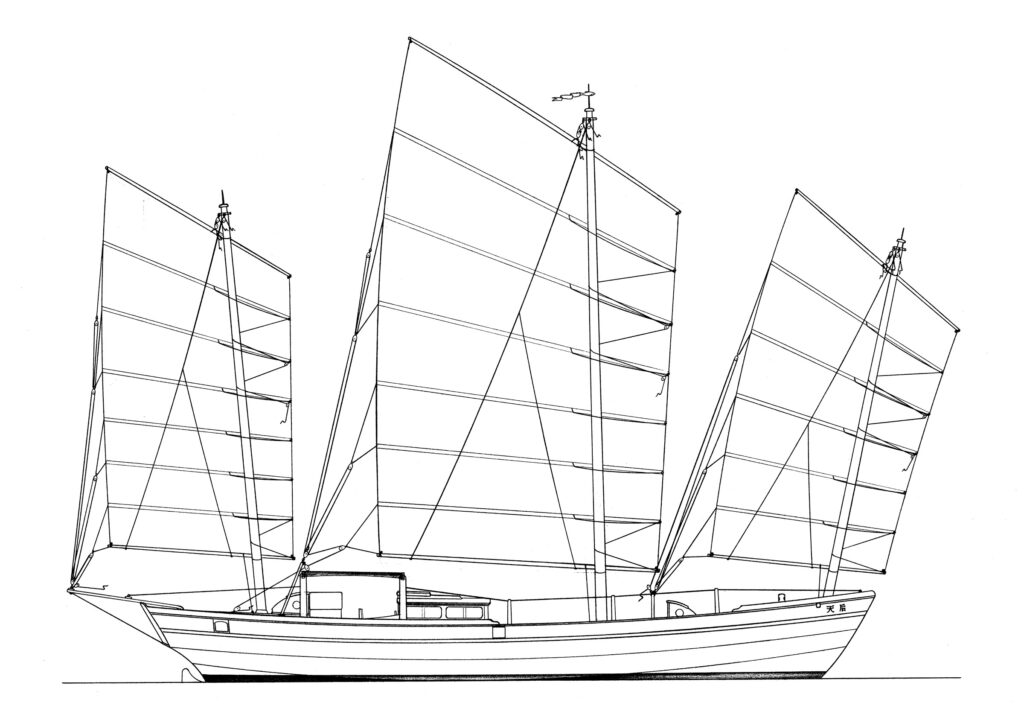

I brought with me two of my closest friends and long-term first mates, Eliot Greenspan and Teresa Rodriguez (for whom I eventually named the new boat). I had just finished my design for a shoal-draft 44’ cat schooner—the Exuma 44. She would become my second cold-molded wood schooner to be built, using a triple-lamination method I had developed, which became the cornerstone for my first book, The New Cold-Molded Boatbuilding. She would also become my second cruising home, and my first shoal-draft wooden centerboard sailboat. All my previous cruising experience had been limited to FISHERS HORNPIPE, which was her diametric opposite.

We cleared a working area on the land, repaired the fish camp, restored water and electricity supply, and pitched a platform tent out on one of the points surrounded on three sides by turquoise water. The camp was a one-room affair, with a derelict kitchen and bathroom. We fixed it up as an office and living/dining area, but the three of us slept in the tent. My late boatbuilding partner Bill Smith, who had worked with me on SARAH in Ft. Pierce in 1984, joined us part time, commuting to the Keys and going home on the weekends. He brought a small tent to sleep in.

We pitched a big open-sided tent for a workshop, and began building the boat outside in the excellent weather typical of a Florida Keys winter.

TERESA in frame, with Tere and Eliot working on her “starter plank”—our tent is just visible in the trees behind

I also hired local people to help us at times, including boatbuilders Doug Gill and Jill Coconaugher, both of whom would work with me on later projects. An Iranian woman named Sholeh joined us near the end, mostly to see what living in a “boatbuilding commune” would be like.

We did have some fun during all the hard work: nude sunbathing and swimming, communal dinners, campfire songfests, love in tents, and windsurfing. I bought a cheap windsurfer at the Dania Marine Flea Market, and Eliot, Tere and I spent frustrating days trying to figure out how to use it… windsurfing is nothing like sailing! It is a fantastic thrill to be screaming over the water, catching a gust, and getting thrown clear over the sail to hit the water at 20 knots! Right next to a 5-foot shark! I finally got to where I could take off from a sitting position on the edge of the dock, and come back 20 minutes later to drop onto the same seat without even getting wet.

The author windsurfing

We really jammed to finish the boat in time to truck her to Rhode Island for the Wooden Boat Show in Newport. I was ripping right through the money I got from the sale of FISHERS HORNPIPE, and I had to promise final payment to some of my helpers upon the sale of the new boat—and I did have every intention of selling her. I was very stressed out near the end, buzzed on massive doses of caffeine, and it was a miracle that Tere and Eliot didn’t kill me in my sleep… except I didn’t have much time for that—near the end we were working day and night.

TERESA being loaded onto a trailer for the trip to Rhode Island; boatbuilder Doug Gill in the foreground

In Rhode Island, we launched TERESA at Point Judith Marina, where I had hauled out the HORNPIPE for her final survey and sale two years previous. The yard owners had become my friends, and I have returned there over the years to visit and work.

TERESA being launched at Point Judith Marina, Rhode Island, in 1985;

With a bouquet of wildflowers to celebrate her birth

I learned the hard way that you are very unlikely to sell a big cruising sailboat at The Wooden Boat Show, and after blowing the last of my money, we departed for the south. On the way we survived Hurricane Gloria in the Mystic River, and capsized in The Mayor’s Cup Schooner Race in a black squall. Despite those misadventures, TERESA turned out to be a fantastic sailboat. She was fast, stiff, surprisingly weatherly, easy and fun to sail, and comfortable to live on, though not quite as comfortable as the HORNPIPE (very few boats are). She easily made 8 knots motoring with her twin Yamaha 9.9hp 4-stroke outboards in wells, to the amazement of all the boats we passed in the Intracoastal Waterway. With the outboards tilted up and hull-plugs in place, and nothing dragging in the water, TERESA was a sailing rocket ship, easily reaching speeds of 10 knots on a reach (her hull speed was 8.5 knots).

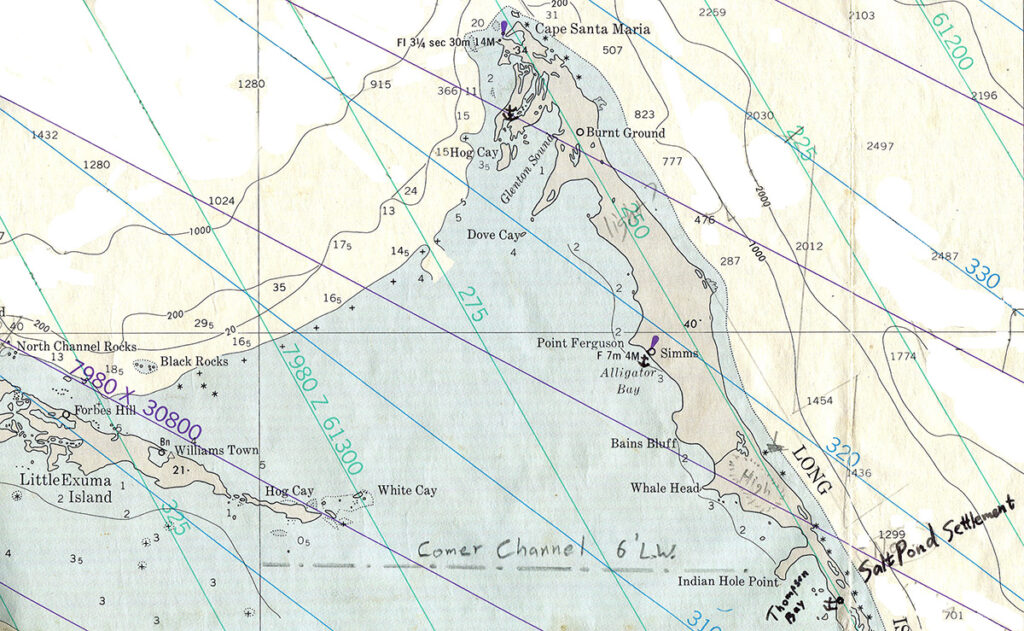

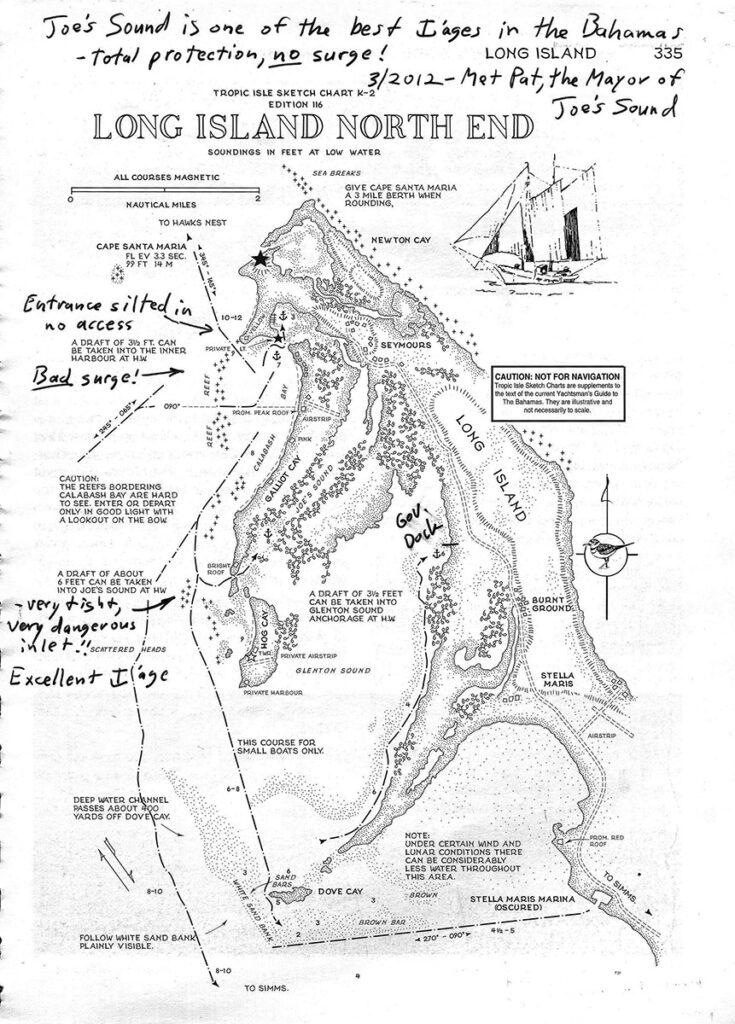

Back in Florida, we picked up some additional ballast in Ft. Pierce, and headed for the Bahamas. We had an excellent first cruise, and the difference in speed and draft from my first boat made cruising a whole new experience. With her draft of 2’ 9” TERESA could navigate small boat channels, lagoons, tidal creeks, and cross dry sand bars at high tide. We had to wave off conventional Tupperware cruisers that tried to follow us, thinking their ridiculous deep draft could manage such a feat. We learned (from experience) that if we ran aground, two of us could jump in the water, put our backs on each side of the bow, and simply push her off using our legs.

TERESA on the beach at Paradise Island with crewmembers Martha on the beach, and Sarah on the forward coachroof

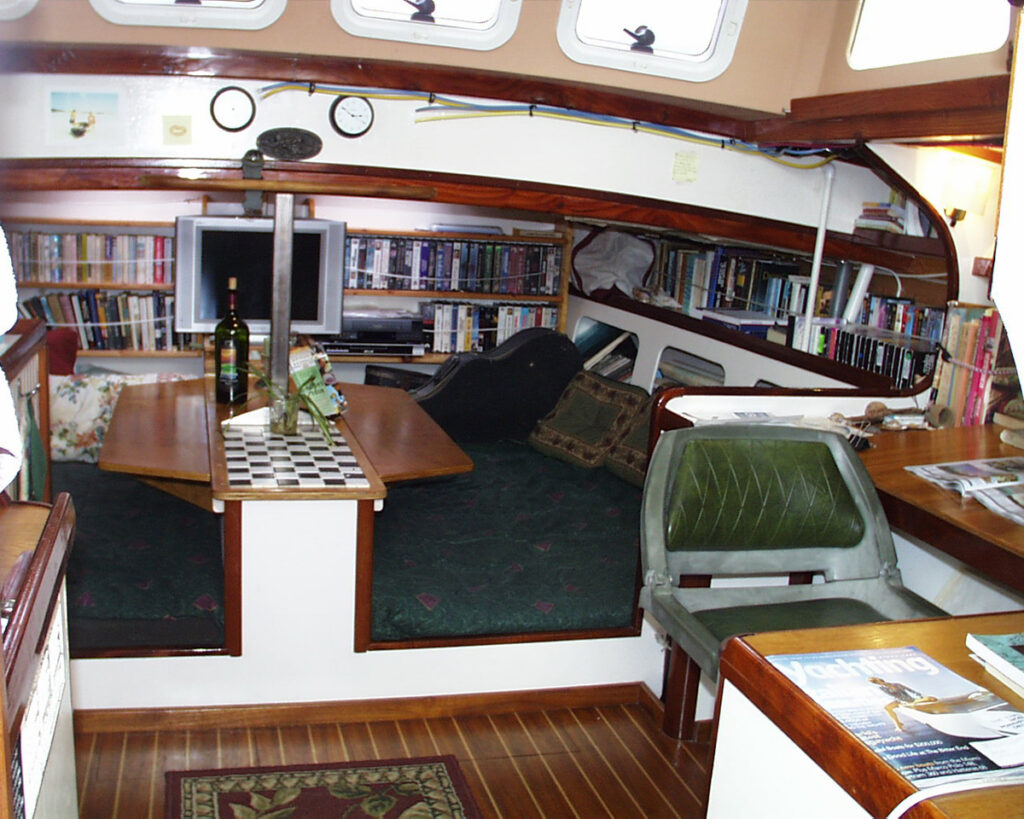

TERESA had a traditional layout, with a “day” cabin aft, and “night” cabin forward. She had four watertight bulkheads as a safety feature, a concept I continue to employ in all my designs. Any cabin can be flooded to the max, and she can still sail or motor home. Her L-shaped galley was large and open, and the whole boat was well-lit and -ventilated. She was a joy to live on.

Crewmembers Pagan Hill and Martha Fitzgerald making lunch in TERESA’s large L-shaped galley with slide-out cutting board (foreground);

Note the charts stored overhead between coachroof beams

TERESA was my first boat to be tiller-steered, and I came to like that at least as much as wheel steering—it is direct and positive, providing excellent awareness and feedback… perhaps a little too much feedback, as she has pretty severe weather helm in strong winds if you neglect to reef her on time! You can steer in reverse also, by simply leaving the tiller opposite the direction you want the stern to go. Water pressure will hold it there.

Pagan and Martha sailing in the Bahamas… Paradise Found!

Note the “tiller comb” used to lock the helm; Pagan has sailed with me since age nine;

Martha went on to become a professional yacht captain – she had never sailed before

In 1986, my first mate Eliot Greenspan and I sailed TERESA downwind across the Gulf Stream in a norther, averaging 10.6 knots against the current (Bimini to Miami). The amazing thing about this passage was that TERESA steered herself! By easing the reefed sails out just forward of the beam – wing and wing – and locking the tiller in the tiller comb, she was perfectly self-steering. I have never sailed another boat that could self-steer downwind. I have never even heard of one! Well … square riggers.

TERESA sailing wing & wing

TERESA running at over 10 knots across the Gulf Stream during a norther;

Eliot at the helm

I lived on and cruised in TERESA for two years, finally selling her to a young couple in the Florida Keys in 1987, who employed her as a six-pack charter boat for the Boy Scouts of America under the name KANGA (they named their dinghy ROO, for which I will never forgive them!). I modified her interior, creating bunk beds in the foc’s’le for the scouts. They in turn sold her to Dave Day, who sailed her to Cuba, and proved how strong her hull is by being driven across two coral reefs in a violent norther, suffering no damage beyond scratches. He eventually sold her to Todd Frizzelle (of Sea Island Boatbuilders), who re-powered her with a Yanmar diesel inboard under the name SHEERWATER, and did a great deal of maintenance and upgrading.

SHEERWATER (ex-TERESA) sailing in the Bahamas

under Todd and Melissa Frizzelle’s ownership

Todd sold her to John Rennell, who renamed her ISLAND GIRL, and he in turn sold her for the last time, to a friend on Man’O’War Cay in the Abacos.

ISLAND GIRL ( ex-TERESA) in Elizabeth Harbor, Bahamas, in 2012

When I was cruising in IBIS in 2012, we got to go sailing on ISLAND GIRL, and she blew my doors off by accelerating to 10 knots on a beam reach in Elizabeth Harbor, putting her lee rail in the turquoise water! What a sweet, sweet ride!

The Exuma 44 TERESA’s Particulars:

L.O.A. 43’ 9”

L.W.L. 40’

BEAM 12’

DRAFT 2’ 8” board up/6’ 1” board down

SAIL AREA 856 sq. ft. working/1520 sq. ft. max.

S A TO DISP 17.45 (working sail)

HULL SPEED 8.5 knots

DISPLACEMENT 22,000 lbs dry

BALLAST 7,000 lbs. lead in a casting under the keel and internal

TYPE Shoal draft centerboard cat schooner

POWER Twin 9.9hp Yamaha 4-cycle outboards in wells (as built)

RIG Cat schooner/Fully battened sails/Self-tending

ACCOMMODATIONS For five/Twin cabins separated by watertight bulkheads/

Vee berths for two; double under the bridge deck/Settee aft

CONSTRUCTION Cold molded wood/epoxy composite

TERESA sailing in Nassau Harbor in 1986, with my dory GANDY DANCER in the stern davits—photo by Capt. John on POOR BUTTLERFLY

TERESA was my “trial horse”—she survived a hurricane (at anchor in the Mystic River, CT), capsized in a race (Mayor’s Cup, NYC), was struck by lightning (Islamorada), and took me on two excellent cruises to the Bahamas and up and down the Atlantic coast. She survived several collisions with reefs, and could be beached just by putting her bow ashore and dropping her centerboard. I miss her—in many ways she was she was the epitome of pragmatic beauty… and she taught me enough to fill a book. She was also the simplest and handiest of all my cruising boats to sail—she was wonderful to single-hand, although definitely not an old man’s boat… she was a wildcat!

TERESA was destroyed in her second hurricane: Hurricane Dorian, in 2019, at Man’O’War Cay, Bahamas.

Now, as old age overtakes me, if I could have any one of my sailboats back, it would probably be TERESA. Old or not – I think I could still sail the hell out of her! With a little female help… .

—Reuel Parker, revised 7/14/2024