A Project in Search of a New Home

By Reuel B. Parker

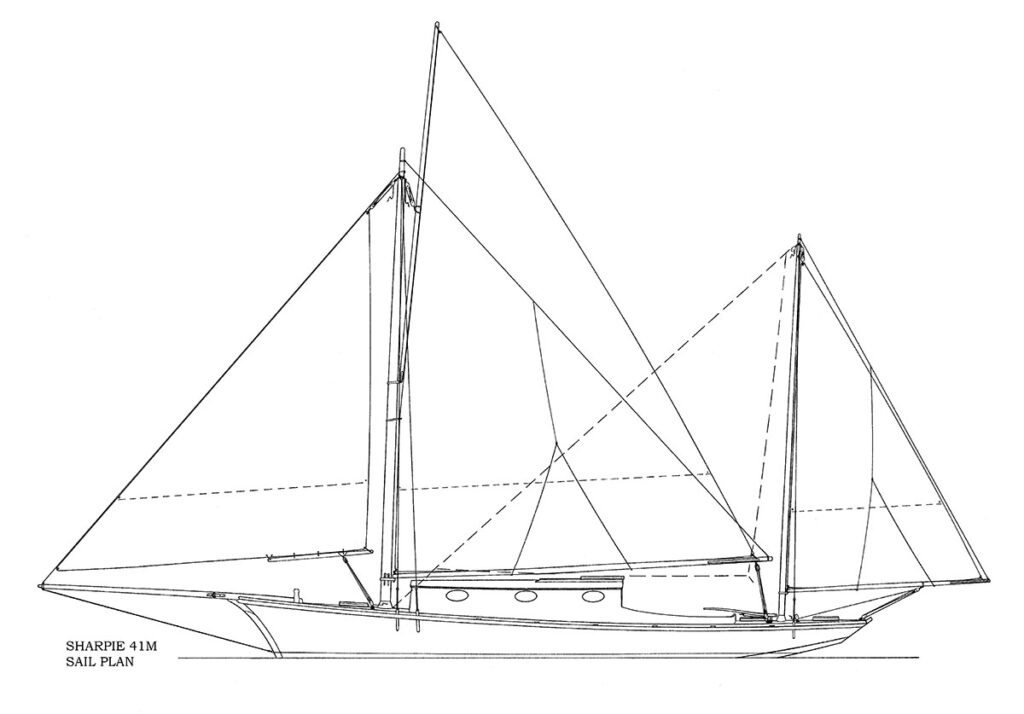

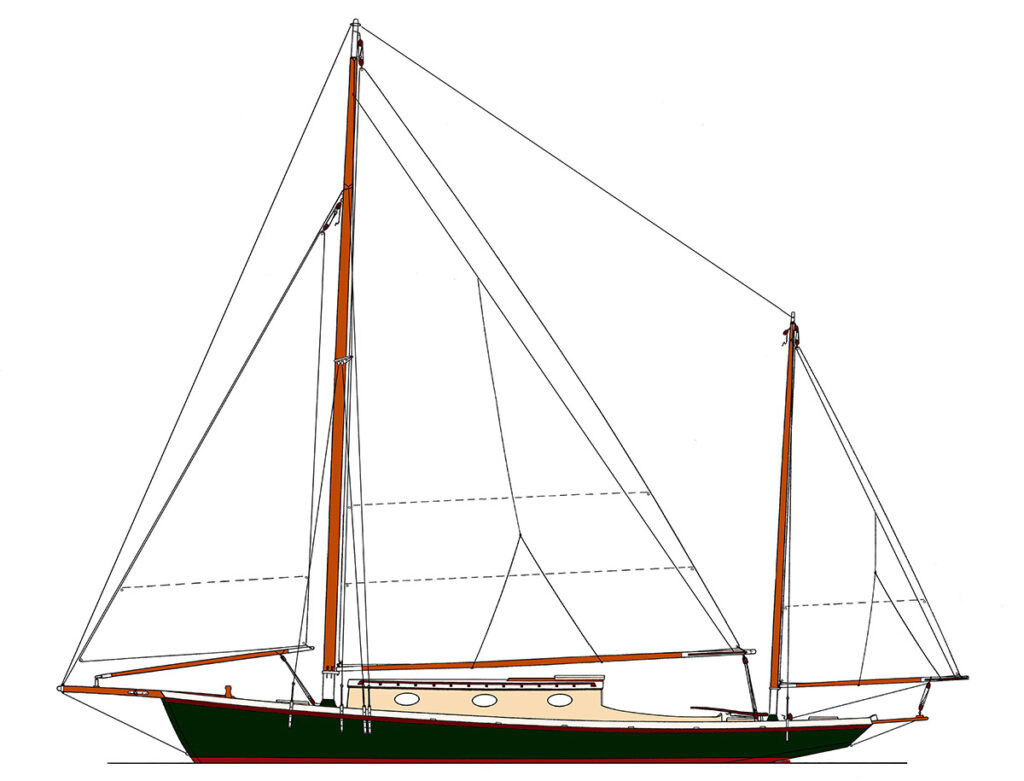

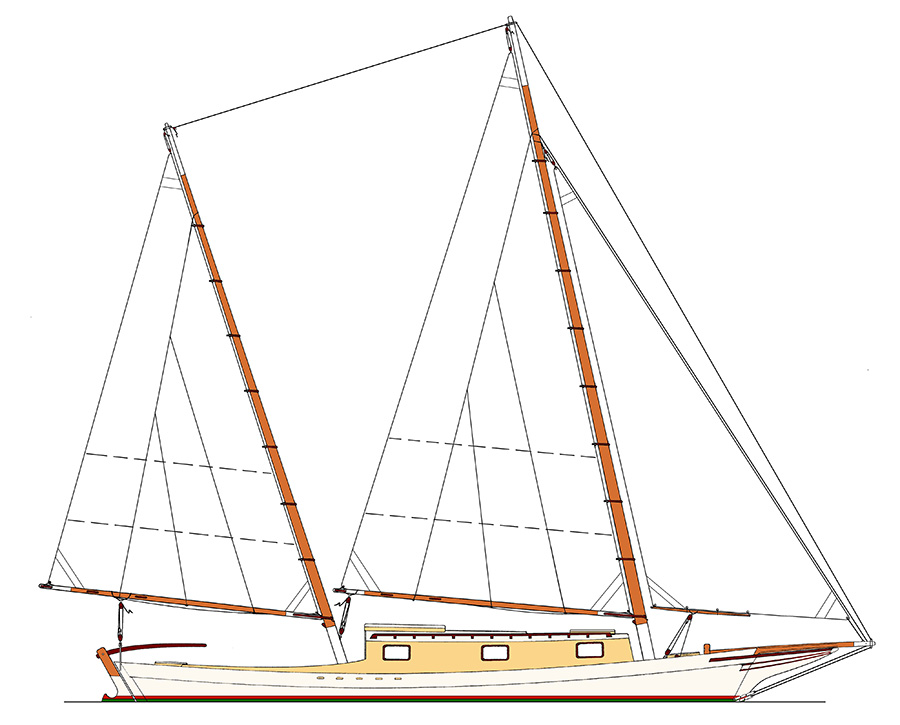

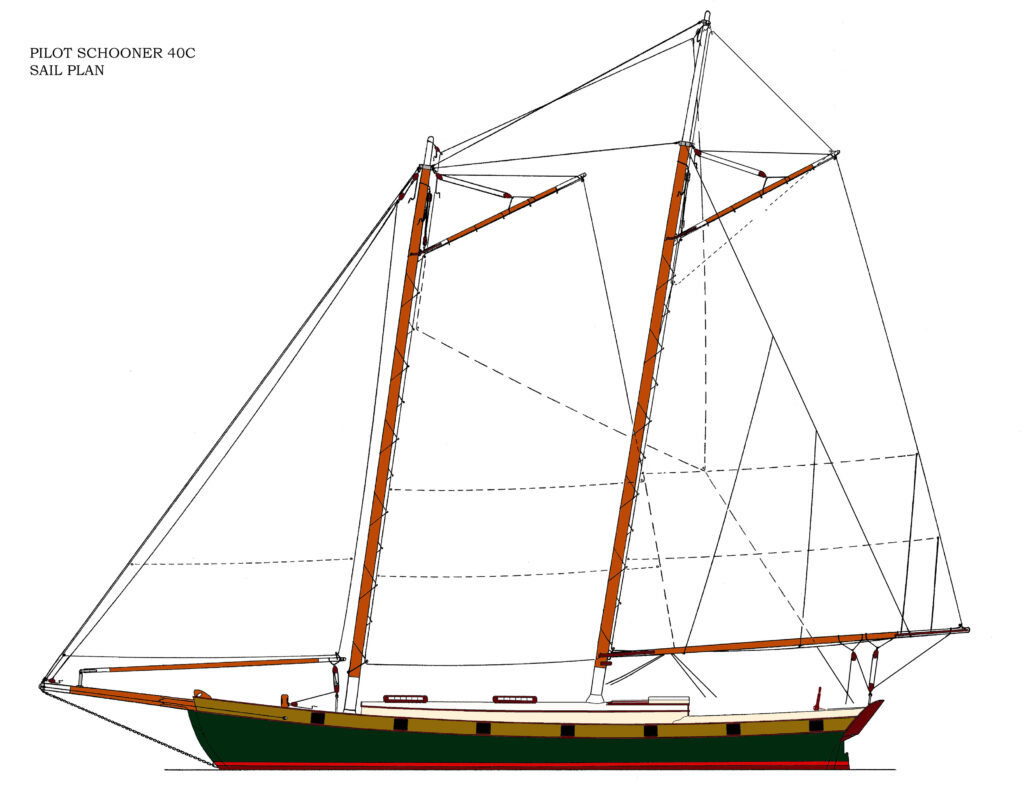

Sail Plan for the Pilot Schooner 40C

In early 2020 I met Chelsea Ragland, who was crewing for Danger Charters. My close friend Wayne Fox, who owned Danger, had put me in touch with Chelsea because she wanted to learn about boatbuilding. Danger runs three charter schooners of my design; one of which I built back in 1984 (the Exuma 52 SARAH).

At the time I was getting ready to sail PEREGRINE, my new cold-molded centerboard ketch, on a cruise to the Bahamas. Chelsea had never been to the islands, so she signed on as crew, giving us lots of time to talk about boatbuilding while enjoying paradise. We chanced to arrive in Bimini 12 hours before the Bahamian government closed the entire country to tourism (due to the Covid 19 pandemic), which made our cruise abbreviated, though we still managed to sail to some beautiful places … especially remote ones where we would have minimal contact with the native population, avoiding the strict regulations the government put into effect.

After we returned stateside, Chelsea contacted a childhood friend from her native Texas, and proposed that she build a cruising sailboat for him, and that I design it and help make it happen. Since I live in midcoast Maine during the summer season, Chelsea and her friend came to visit me at home, where we discussed the boatbuilding project. We chose my Pilot Schooner designs as a “point of departure,” and together worked out the parameters that would satisfy our client, and implement Chelsea’s boatbuilding dream.

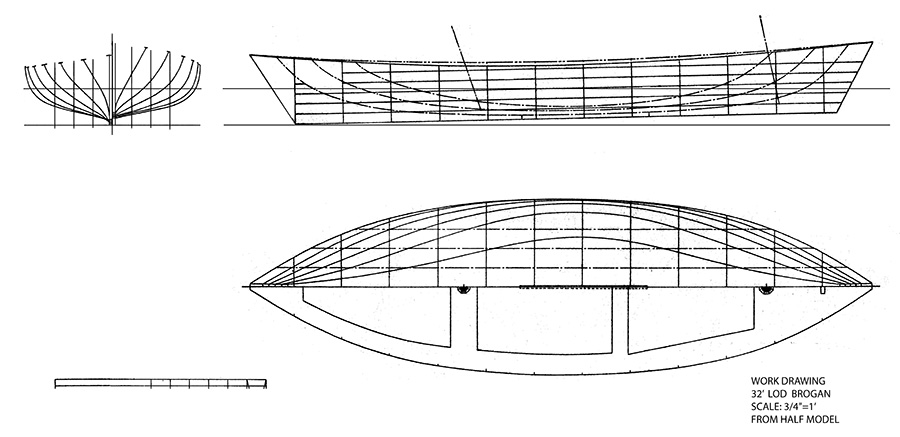

For the schooner’s design, I worked from my Pilot Schooner 45 plans, creating a smaller version. The vessel that emerged would be cold-molded in Port Orford cedar, supplied by Americas Woods, a distributor of boatbuilding lumber in Washington, Maine. Construction would be triple-laminated using the methods described in my first book, The New Cold-Molded Boatbuilding.

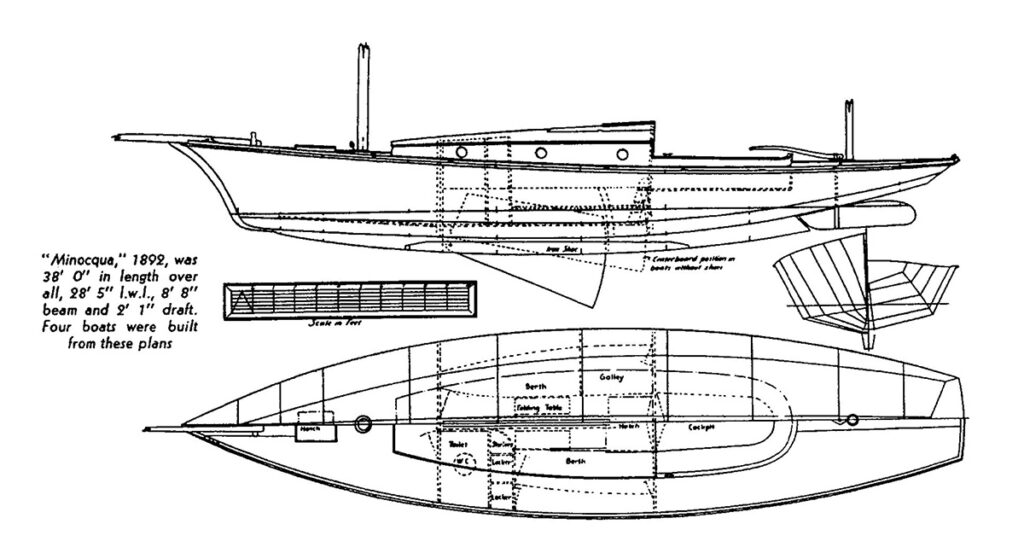

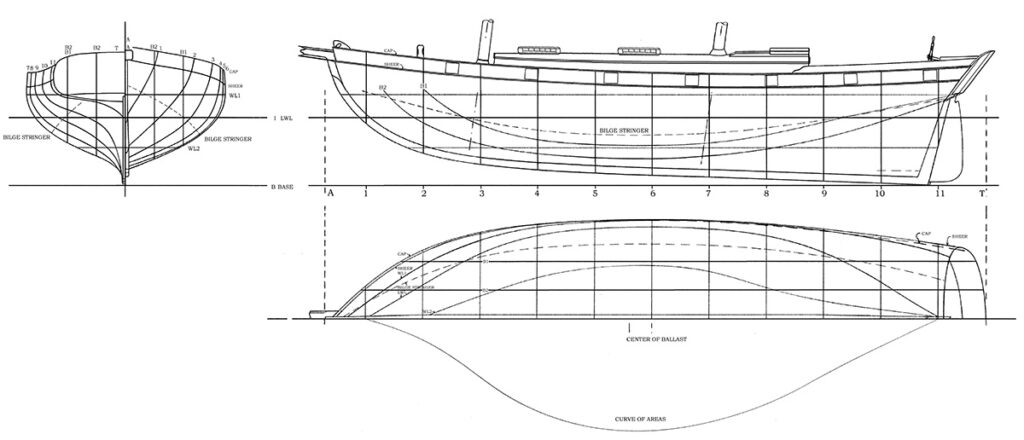

Partial Lines for the Pilot Schooner 40C

Specifications are as follows:

L.O.A. 40′

L. EXT. 54′

L.W.L. 35′ 6 1/2″

BEAM 12′

DRAFT 4′ 2”

DISPL. 27,500 lbs. (13 U.S. tons) Laden

BALLAST 9,500 lbs. Lead (3,750 lbs outside; 5,000 lbs inside; remainder in tankage and trim)

SAIL AREA 914 sq ft working/1,254 sq ft total (light air)

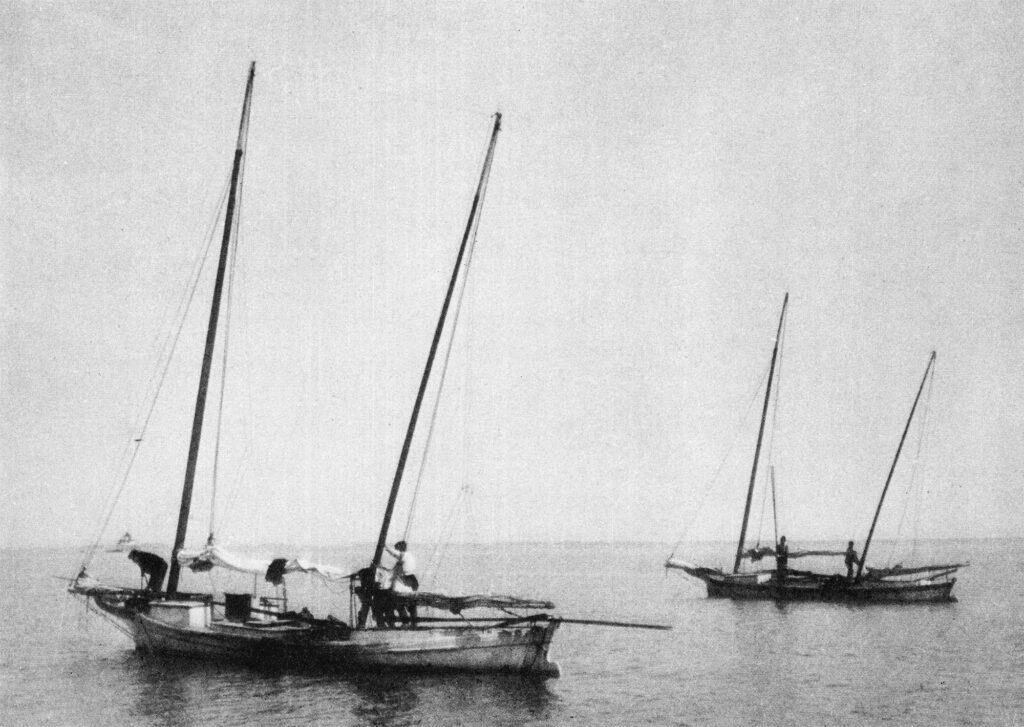

TYPE Full-keel pilot schooner yacht based on early 19th-century

Virginia models (Baltimore Clippers). Hull Speed: 8 knots

POWER Inboard diesel, 40 to 60 H.P., under cockpit well

RIG Free-standing gaff rigged schooner with overlapping fores’l, self-tending jib and light air fisherman tops’l. The jib may be set flying with luff tension provided by a downhaul; or may use roller furling. The traditional jib is lowered by luffing up, releasing the halyard and tack downhaul, and stuffing the sail and club-foot into the fore-hatch. The roller furling jib may have doubled sheets or may be sheeted to the boom shown. The mains’l clew may be seized to a ring which slides forward when the outhaul is slacked, bringing the mains’l on deck OR may be reefed/furled to the boom if full-length battens are employed (suggested). This rig is one of the simplest ever conceived; yet it has power, versatility, practicality and economy. Howard Chapelle felt it should be revived for use in cruising yachts because of these qualities, without modification. So do I!

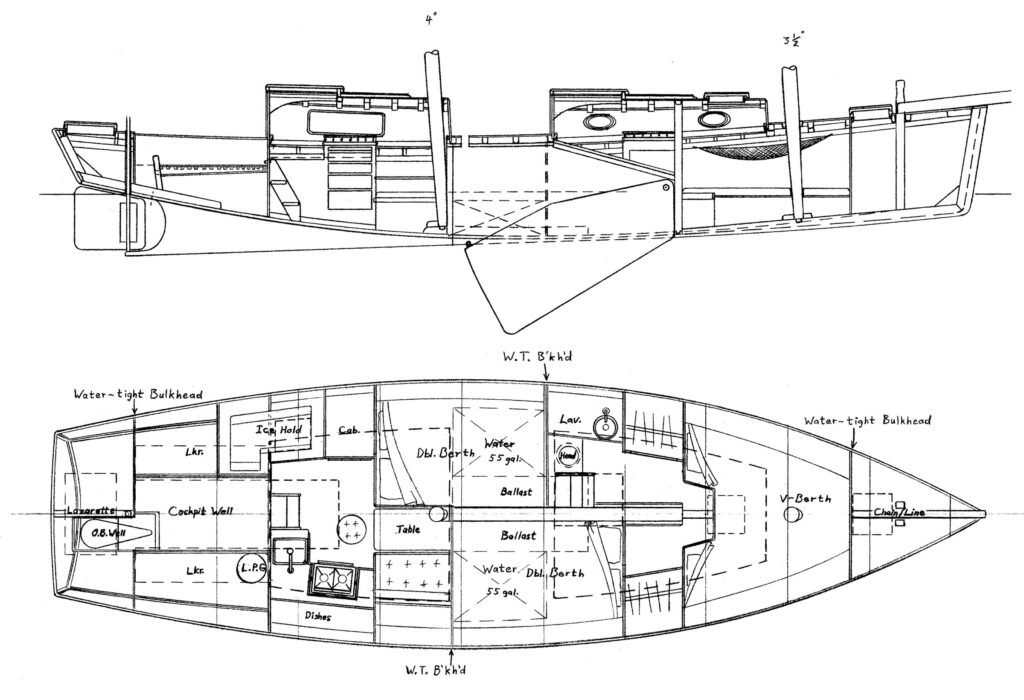

ACCOMMODATIONS Interiors (2) shown sleep five. Double cabin aft. Head/shower forward. This is a comfortable, practical vessel, capable of extended ocean cruising anywhere in the world. Water capacity is 100 gal or more with a second tank under the hold. Fuel capacity is 200 gallons or 300 gallons (Alt. Plan).

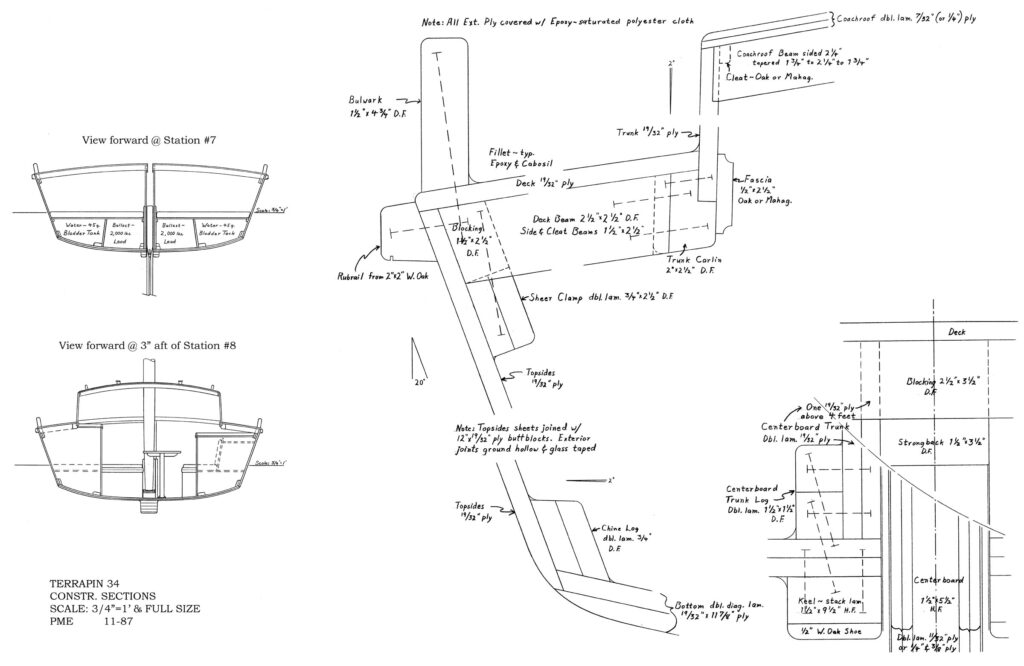

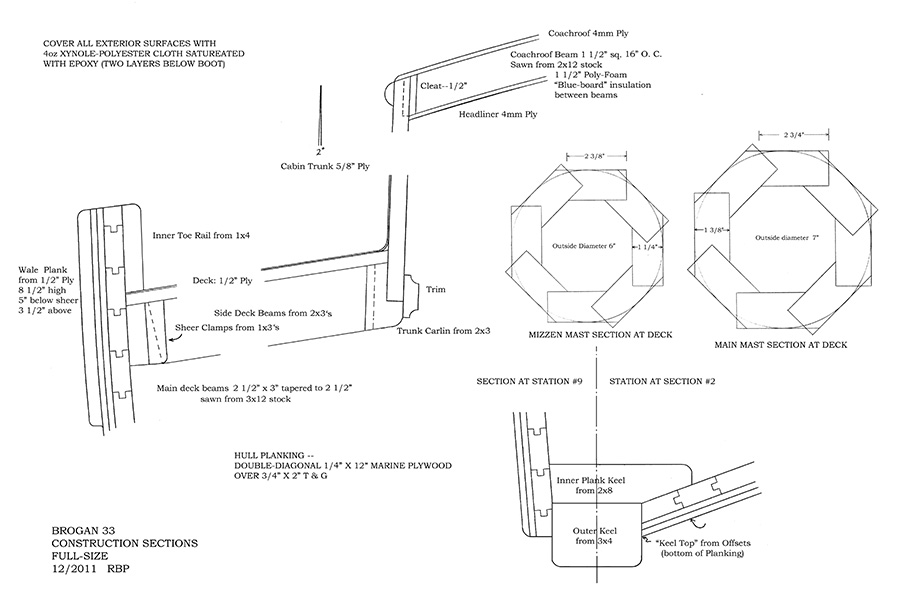

CONSTRUCTION Cold-molded wood/epoxy/fabric: Hull — double diagonal 5/16″

marine ply or solid planks over 3/4″ tongue and groove lumber. Outside Xynole-polyester covered; two layers below boot top. Decks – 1/2″ ply over sawn beams, Xynole-polyester covered. Coachroofs — 3/8″ ply. Masts are hollow octagonal free-standing Douglas fir, booms and gaffs are solid Douglas fir. Interior — painted plywood trimmed with varnished hardwoods.

I designed an interior plan based on our client’s parameters, but later changed it to the more traditional arrangement shown here:

Plan & Inboard Profile for the Pilot Schooner 40C

I elected to divide the ballast between a steel box keel filled with fitted blocks of solid lead, and inside ballast placed on the keel below the cabin sole. With a ballast ratio of 34%, this will be a very stiff hull, with righting moments beyond full capsize. But with moderate draft (4’ 2”), and ballast relatively high (compared to modern yachts), the motion of this schooner will be much gentler than for most yachts. Strongly raked, free standing masts of moderate height also indicate gentle motion.

Accommodation is for four people, with a large settee available for a fifth. The design also includes a cargo hold/food pantry with a second large optional integral water tank below it. The schooner will carry enough water, stores and fuel for long-range cruising. She will not be fast (hull speed is 8 knots), but she will be powerful, comfortable, and eminently seaworthy. She can go anywhere. She will stand up under her canvas, and carry it longer than most yachts. And the schooner rig has more options for carrying additional sail than any other rig. A little-known feature of free-standing masts is that by letting the sails out just forward of the beam, the vessel will steer herself downwind. And with the helm lashed on a beat, she will steer herself upwind. And the reef points will have full-length battens immediately above them.

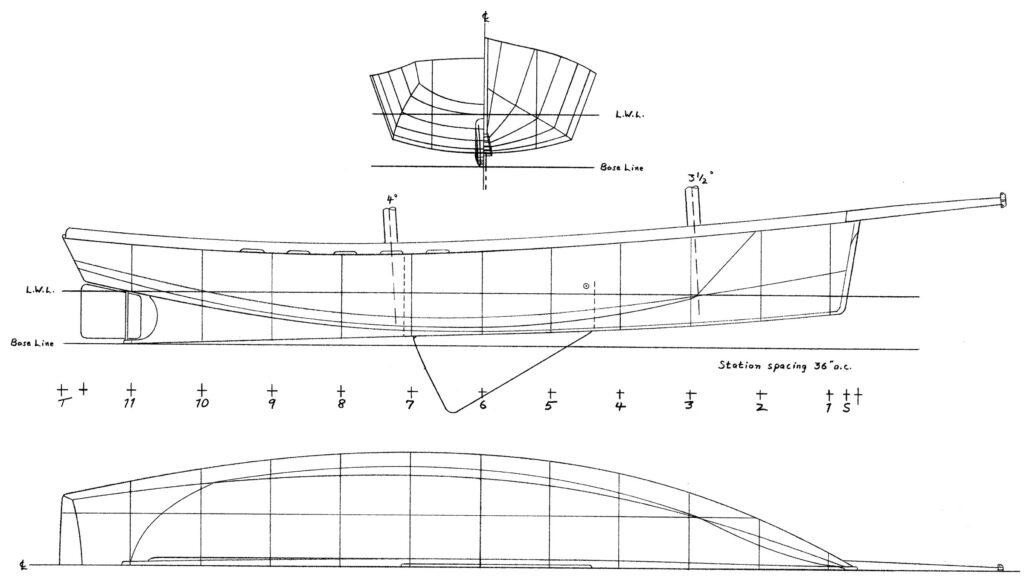

Construction Sections for the Pilot Schooner 40

Whereas I often specify marine plywood for the diagonal planking, for this build we opted to use solid Port Orford cedar milled to 5/16’ X 5 3/8” planks – a convenient size for diagonal planking a very “curvy” hullform – also convenient to mill from Americas Woods’ available stock. The hull would employ solid Douglas fir and pressure-treated pine for the backbone – inner keel, apron, horn timber, knees, etc. Bulkheads would be 5/8” marine plywood, some of which were conveniently located at design stations. Remaining design stations were made from mold frames in the conventional manner.

I introduced Chelsea and our client to my friends at Hylan and Brown Boatbuilding, and we arranged for workspace in their yard, including help from one of their professional boatbuilders, and use of their large bench tools.

In July of 2020, construction got started, materials were ordered (epoxy and related products were shipped from Florida), and summer was in full bloom. Chelsea and I lofted the schooner’s design stations on two sheets of MDO plywood, the Strong Back was laid, bulkheads cut out, and design-station frames built. The frame was erected on the strong back, and with backbone, sheer clamps and bilge stringers, the hull began to take shape. I worked hands-on in the beginning, then shifted to advisory status as the work progressed. Finally, Chelsea kicked me out because I was old and in the way!

The Pilot Schooner 40C hull in frame

By early Fall, the bare hull was planked, without stem, outer keel, or sternpost. At that point, with cold weather rapidly encroaching, Chelsea had to decide whether to store the hull in a friend’s barn for the winter, or have it shipped to my shop in Florida, where she could continue working on it. She decided on the latter, which would include hiring my late partner Bill Smith to help her, fabricating all metal parts including a steel box keel for outside ballast, help with cabinetry, systems, etc. I would help part time with spar-making, rigging, machinery, and systems also.

The bare schooner hull arriving at my shop in Riverside Marina, Florida

When the hull arrived in Florida, we unloaded it, plus various remaining supplies. We blocked the hull upside down in my work space, and began organizing our seasonal work plan. Chelsea arrived soon after. And at that point, our client pulled the plug on the project, for reasons that were never explained, and left the three of us without work. This destroyed the very tight schedule that would be required to accomplish our goals through the winter work season. All three of us had arranged our lives around this project, and suddenly we were left swinging in the breeze. This was particularly devastating for Bill, who had cancelled other work projects for this one, and was left suddenly unemployed.

Many weeks went by, with Chelsea trying to get the project back on track. In the end, our client – really Chelsea’s client – made a number of severe and vulgar accusations against Chelsea, causing her severe stress and unhappiness, and completely terminating the project. He abandoned the whole thing, leaving the hull stranded in my work space. He declined to pay rent on the space, refused to reclaim his property (we were all owed money), and terminated all communication.

Eventually we had the hull moved to my friend David Halladay’s “Boatsmith” facility in Jupiter, Florida. My late partner, Bill Smith, had made the steel box that would contain outside ballast, which was also moved to Boatsmith.

At the time of this writing, in early February of 2024, the hull is likely to be moved again, this time to a friend’s storage facility in Tampa, Florida.

The purpose of this article is to offer this project to someone who has the resources, abilities, and drive to complete it. I am offering the bare hull, with the box keel, for sale for $10,000. The package includes a full set of plans for the project.