By Reuel Parker

The author’s first cruising sailboat, FISHERS HORNPIPE

On June 7th at 1830, we left Puerto Plata, Dominican Republic, to continue our long beat eastward. Our destination was Mayaguez, Puerto Rico. That first night—perhaps you have noticed that we almost always began voyages at night—was a very rough beat in 20 knots of ESE wind. An hour out we blew the tack pennant on the genoa jib, and had to wrestle it down in the moonlight, then put up the yankee and the stays’l. We were carrying a lot of sail, driving the boat very hard, trying to make good time and close tacks. Early the next morning the wind eased off a little, and the sailing was gentler. We beat to windward for three days, having all kinds of wind from calms to squalls, and finally tied up to the Commercial Wharf at Mayaguez. The Mona Passage had lived up to its notorious reputation—rougher than shit and full of freak waves, unpredictable winds and dangerous currents.

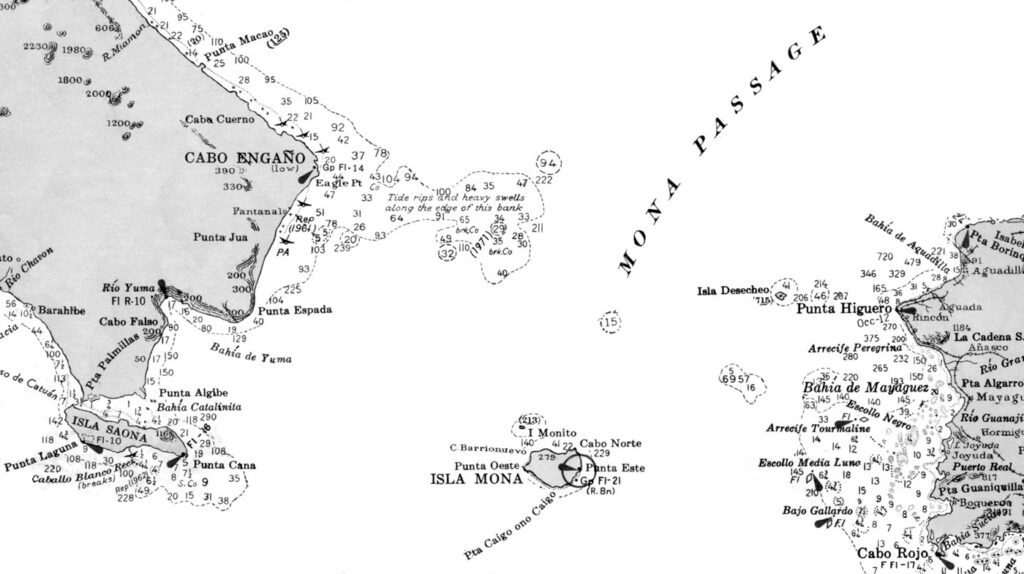

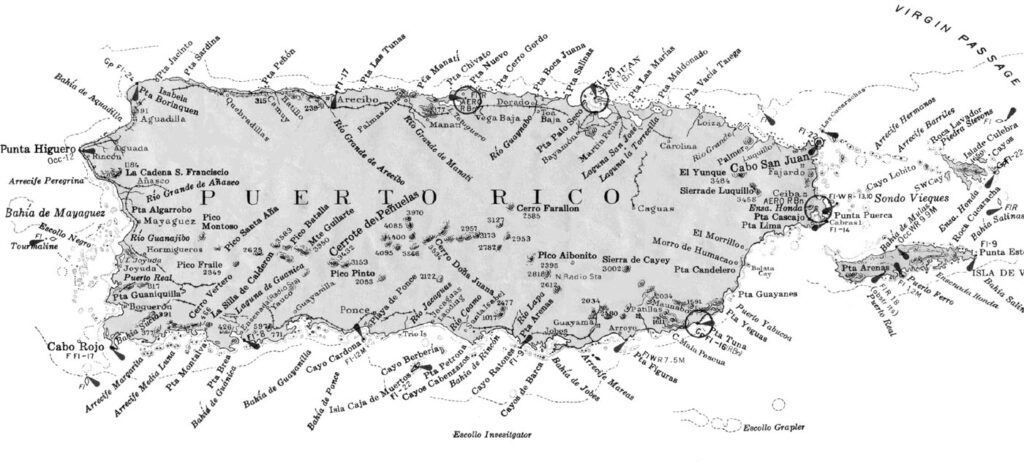

The Mona Passage, between Hispaniola and Puerto Rico—a place of strong winds, powerful and often unpredictable currents, and rough seas. Boquerón, which we visited longest, is in the SW corner of Puerto Rico, just above Cabo Rojo.

The reasons for night departures are several: Often a passage is likely to be longer than twelve hours, making it impossible to enter a new, unknown harbor in daylight. Entering in darkness is manifestly risky—even if a harbor has well-marked channels with lighted buoys, the mariner simply cannot see all possible dangers. Also, port officials do not generally work at night, and in some countries, it is frowned upon, if not illegal, to enter a port without clearing in almost immediately. Finally, night winds, in much of the world, are gentler than day winds—hence seas may be smaller and gentler too.

We were all immediately intrigued with Puerto Rico. The people are proud of their reputation for hospitality, and they certainly proved it by us. Virtually everyone we met was kind, warm and generous. People seemed to always go out of their way to be helpful, and this was true of everyplace we went on the island. Quite a contrast to some of your New York City ‘Ricans! (I say this having had a knife to my throat, having been robbed, and having been beaten up because I couldn’t speak Spanish—all in New York.) What was also intriguing was knowing that we were Americans in America—sort of—and that Spanish was definitely the national language. I fell in love with Puerto Rico, and will always return there.

On the 12th we sailed down the coast to Bahia de Boquerón, and anchored off the village. We had wanted to visit quaint Puerto Real—but the harbor looked too narrow and shallow to me from sea, and I chickened out. Some of our cruising pals were at Boquerón—Satisfaction and Allonz-Y—and we soon made friends with the people on boats that were new to us.

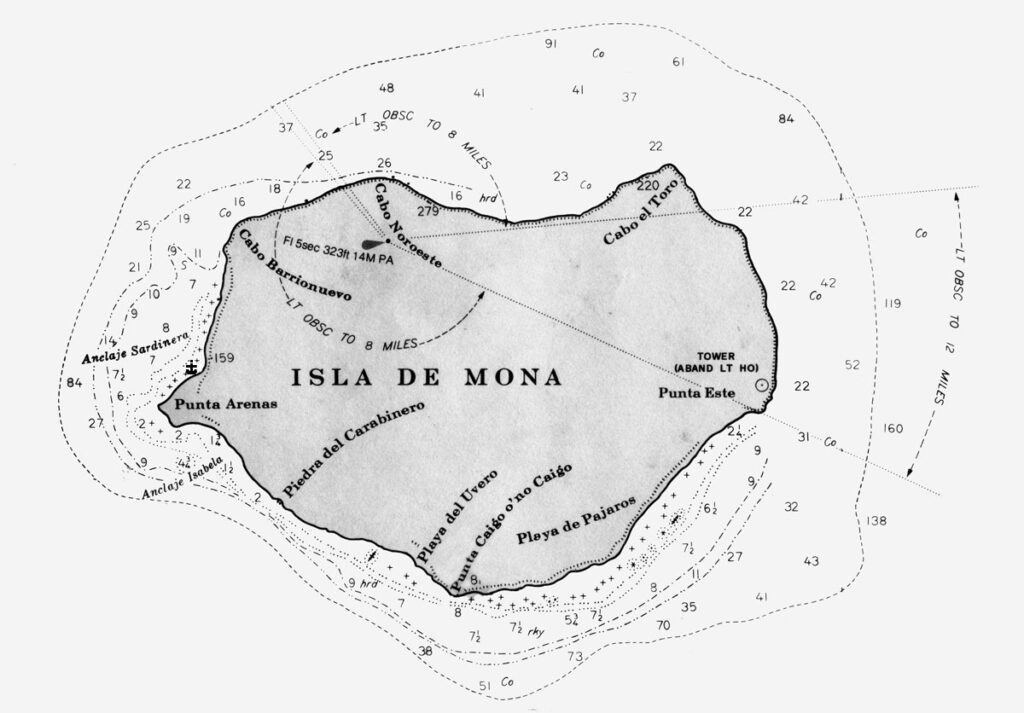

Everyone was talking about Isla del Mona, in the middle of the Mona Passage between Hispaniola and Puerto Rico, and I wanted to go visit it. None of the other boats had dared attempt a visit—in addition to the rough, potentially dangerous passage, Mona has no real anchorage. The island, roughly seven miles in diameter and more or less round, consists primarily of steep, rocky cliffs. Only on the west side—usually the lee side in the easterly Trade Winds—is there a beach, protected by a small reef which forms a tiny basin. There is a single, narrow break in the reef, through which it is just possible to run a small vessel. Once inside, you must round up and anchor immediately, and there is only room for two or three small boats. If for some reason the wind shifts to the west—which it can do during storms—any vessels in this anchorage find themselves right on a lee shore, with virtually no protection from storm seas which sweep over the narrow reef and break across the basin. You can see why no-one goes there. So we had to!

As we talked about our proposed adventure in the anchorage and in the village, we soon found many others who wanted to go also, but had been afraid to. So we put together an expedition crew, which consisted of the following:

Fishers Hornpipe Paul, Loretta, Stacy, Reuel

Satisfaction Shawn, Cheryl (12-year-old twins)

Allonz-Y Irene

Nail Cakes Jim

Blue Boat Ross

Boquerón Village Minerva

Ten people was quite a large crew for the Hornpipe—but the tropical weather was such that most of them would sleep on deck. If it rained, we had the settee in the great aft cabin, which could sleep three, and we could sleep six in our cabins, assuming people didn’t mind sharing berths. I admit that I wanted Minerva to share mine, but she wasn’t interested. I later learned why, possibly, when I met and became friends with her ex-boyfriend and father of her son. She was still working things out with him, it seemed. Or perhaps she just knew better than to get involved with a transient hippy sailor who would soon sail away. Finally, there is the distinct possibility that she was only interested in becoming friends with me, and nothing more. I asked her if she had any interest in cruising, and she replied that it just wasn’t something she wanted to do then, particularly with a six-year-old.

I first saw Minerva sailing across the Bay (Boquerón is quite large) on her Sunfish in a 20-knot trade wind breeze. She was wearing a bikini, and was hiked way out to windward to hold the hull of her little boat flat to the water so it would plane. She was leaning way back over the water—so far that she could dip her head and long black hair into the sea. She was so alive and so beautiful and so totally a sailor that my heart jumped into my throat and thumped like hell. I was out sailing in Gandy Dancer, and though I tried, I couldn’t catch her.

On the 16th at 1915, we departed Boquerón with our crew of ten and sailed to Isla del Mona. The passage was rough in confused seas, and we rolled heavily running downwind wing and wing, although the winds were pretty light—around 10 knots. At 0340 we came right up on Mona—having never seen the tiny light on the cliffs—and had to jibe quickly to run north around the island. As we ran along the vertical gray cliffs that encircle most of the island, we could see, even in the dark, that they were riddled with caves. Above, there was verdant tropical vegetation pouring over the cliff tops. At 0640 we carefully entered the tiny basin and anchored. The view we saw with the rising sun was one of the most beautiful imaginable.

Isla del Mona (Puerto Rico). We anchored in Anclaje Sardinera, off the ranger station. The island is riddled with caves, giant Iguanas, and is a National Park.

Since I had been up all night, I went below to my cabin to get some sleep. We had caught a fish on the way in, and someone was cleaning it on deck above my cabin, after which they dumped a bucket of salt water on the deck to rinse off. Fishers Hornpipe has portlights set into her hull just below her rubrails, and the one in my cabin was open to get some fresh air. I woke up with a shock, screaming bloody murder as several gallons of salt water, fish guts, blood, and scales came cascading all over my naked butt—to say nothing of my bed!

It took two trips in Gandy Dancer to ferry everyone ashore—though a couple of people swam in to the crescent white-sand beach. On shore we met the island’s Puerto Rican park-caretaker, who was fluent in English. Paul—a lifelong fan of iguanas—immediately wandered off in search of some. He quickly came back, holding his hands as far apart as they would go, looking a little dazed and muttering strange imprecations…. The park ranger started laughing—he knew Paul had seen a legendary giant iguana!

The ranger (only inhabitant of Isla del Mona) took us to see several of the famous caves. This time we remembered to bring flashlights! The caves were huge, amazing, and plentiful. Indeed, the whole island was riddled with caves, and we later heard of a legendary secret expedition in which some geology students from Puerto Rico had traversed the whole island underground through caves, having to accomplish large parts of the journey with scuba gear.

We took long walks in the jungle rainforest, and the plant and animal life were astounding. I felt as though I had stepped back in time a million years. I remember looking into a huge bromeliad, full of rain water, and seeing a tiny multi-colored frog the size of my little fingernail. I realized that each bromeliad contained its own miniature eco-system.

During all my travels to remote places in Fishers Hornpipe, I became more and more convinced that the most important challenge facing humanity is the preservation of the Natural Earth, of biodiversity, and of wilderness areas for their own sake. These feelings were not new—they were fundamental to everyone at Starhill—but they were growing ever more important, ever more urgent, in my mind and spirit. [They continue to do so.]

At 1805 we regretfully left Isla del Mona, and began the long night sail to windward back to Boquerón. Just as I started the Hornpipe’s diesel, the raw water pump died, spraying salt water all over everything in the engine compartment, and I had to shut it down. I explained to everyone that we had just become a “true” sailing vessel. We would have to leave this very tight spot under sail alone, and beat back ‘home.’ We raised the main, paid out the main sheet so we would be able to turn downwind to get out, and had crew ready to raise jib and stays’l the moment our anchor broke the surface. Which turned out to be a problem, as the anchor wouldn’t let go of the bottom! This time Paul was spared, as Shawn immediately jumped overboard. Not only did he free the anchor, but he also came up with a large “bug” (spiny crayfish), proclaiming excitedly “they’re all over the place down there!” We slipped the “bug” surreptitiously into a bucket and I told Shawn to leave the others in peace—we were, after all, in a park, and all wildlife was protected.

Once again in the Mona Passage, we had a rough ride in the intersecting cross-seas and swirling currents. But Jim took that bug below and made lobster crepes! He was a real trooper to cook under those conditions, and I wasn’t surprised when he hurried on deck and tossed his cookies. Jim was a commercial fisherman—you know it’s rough out when a commercial fisherman barfs! We tacked into 15 to 20 knot trade winds all night, and at dawn, as we approached Puerto Rico, the wind died. We were 20 miles from Boquerón, and we couldn’t get there! We would catch a puff and start sailing only to have the powerful currents carry us away. We tried different approaches—went back out in the Mona Passage and tried to find lasting wind. We tried to find less current. Nothing worked. It took us 15 hours to cover the last 20 miles! Finally, at 1820, we anchored off the village, and a very tired—but not unhappy—crew went home for a long sleep.

Loretta had a troublesome love affair in Puerto Rico, and ran out of money at about the same time. She left us to go work in San Juan, the capitol city on the north coast. She was gone, but not forgotten, and we got back together later, thousands of miles away.

Puerto Rico, Isla Culebra and Sondo Vieques. Isla Caja de Muertos, which Paul and I explored, is in the middle south coast. We cruised all but the north coast.

Paul and I had been eyeing a very beautiful 30’ sloop beached by one of the previous year’s hurricanes—and we were so reminded of Tony’s Malabar Jr. Imagine that we started planning how we might save her. The boat was rough, but structurally sound, as the storm surge had simply put her up on the beach unharmed. It turns out she had been the last boat built by an elderly master shipwright in Puerto Real, who had since died. The little sloop had been used as a commercial fisherman, and had a large diesel engine in her—and nothing else. After asking around town, we located her owner, who offered to give her to Paul if we would remove her diesel and return it to him. Someone else had taken her sails, and told us we could have them back. Another man who had a restaurant nearby told us we could restore her in his yard—for free—and that he would help us buy materials for the work. I made some drawings for converting and restoring the sloop as a pocket-cruiser, and Paul became very excited about having his own boat. Unfortunately, when he called his folks back in the states to ask for money to finance the project, they said absolutely not. We sadly had to thank everyone for their kindness, and leave this rare jewel to rot on the beach.

The new raw water pump for my diesel cost $130 to replace—and I was lucky to find one. We stayed a month in Boquerón, and became so comfortable there that it was difficult to leave. We even left one time, spent the night in La Parguera, and came back, as Paul became sick.

While in Parguera, we met up with a woman introduced to us earlier by Minerva, who was attending the oceanographic institute there. She gave me a guided tour of all the marine biology projects, and that night she took us to Bahia de Phosphoro—the most phosphorescent place on Earth—in her outboard-powered skiff. It was a dark night, with no moon, and I stayed on the bow watching the lightning flashes of fish darting out of our way. Then she anchored, and we all took our clothes off to swim. I will never forget the beautiful glowing image of her naked body as she dove into the crystal clear water.

From THE VOYAGES OF FISHERS HORNPIPE, by Reuel B. Parker